Marie Donahue: Great. I’d love to dig into that some more, with maybe some examples of what that engaged scholarship looks like for you. I’m sure, as a faculty member, there’s a lot on your plate, but how are you approaching that in the context of some projects?

Gabe Chan: Yeah, I could talk about a couple of our projects or initiatives that we have going on. One of the big things that we've been working on recently is work with electric cooperatives in the region. Electric cooperatives are interesting because they're like private utilities but they're owned by their consumers. Electric cooperatives don't have customers, they have member owners. We've been doing work with a number of cooperatives in the upper Midwest for the last several years, and some of that work has been supported by the Department of Energy through a program they’ve called the Solar Energy Innovation Network and funded in other ways, through foundations and such. But what’s really exciting is that these utility cooperatives are really important across the country. They serve a little under 15% of all people, but in the Midwest they serve an even higher percentage, and they serve mostly rural areas.

And these retailers are really different from investor-owned utilities. They're not regulated in the same way, to the same extent as investor owned utilities, because they are self-governed and through that self-governance, they have a lot of institutional structure. A lot of rules for how they operate as democratically controlled organizations, meaning that they have different practices, different incentives, different ways of operating and returning back value to their communities, than other types of utilities. And they’re nonprofits, or more accurately, they are not-for-profit utilities.

These are interesting because they have so much potential to act quickly and innovate new programs as CERTs has documented in this podcast and elsewhere, they have a lot of really innovative programs. One of the things I love about CERTs is the storytelling that goes on because you have these innovations happening in small rural utilities that they don't like to brag about. It's hard to get the word out, and I think it's really good to tell that story.

The work we’re doing with cooperatives, there's really been a lot of work on how we can work within the cooperative structure to find new opportunities for innovation. Particularly, as we're seeing cheaper renewables come online, as we're seeing wholesale markets like here in the Midwest, the MISO market, creating new opportunities for distributed energy resources, and other ways of procuring power. These market developments in technology, I think, have really been structured around a paradigm of investor owned utilities, and there hasn't yet been a clear pathway or clear mode of engagement for cooperatives to identify and then capture the opportunities that these technological and market changes are presenting.

We’re thinking, how can we work together with cooperatives in their existing structures, which oftentimes involves a local distribution utility and then a larger what's called a generation and transmission (G&T) cooperative utility. How can they work together to find these opportunities? We're looking to support the work of cooperatives through things like developing new analytic tools that help assess the opportunities of distributed energy resources, like solar energy, but also doing work like interviews and focus groups. Working with groups of distribution utilities to see really what's important to them. What do they need from their larger association in the G&T—the generation and transmission family—in order to thrive here, and how can you navigate differences? Sometimes the G&Ts role—to use the terrible analogy—seems like herding cats across members, which I think actually is not accurate. I think oftentimes it's much more about how we can better listen to, get participation from, get buy-in, fine-tailor solutions, and innovate as technology and markets are changing to really support everyone and continue to drive a lot of value for rural communities all across the state.

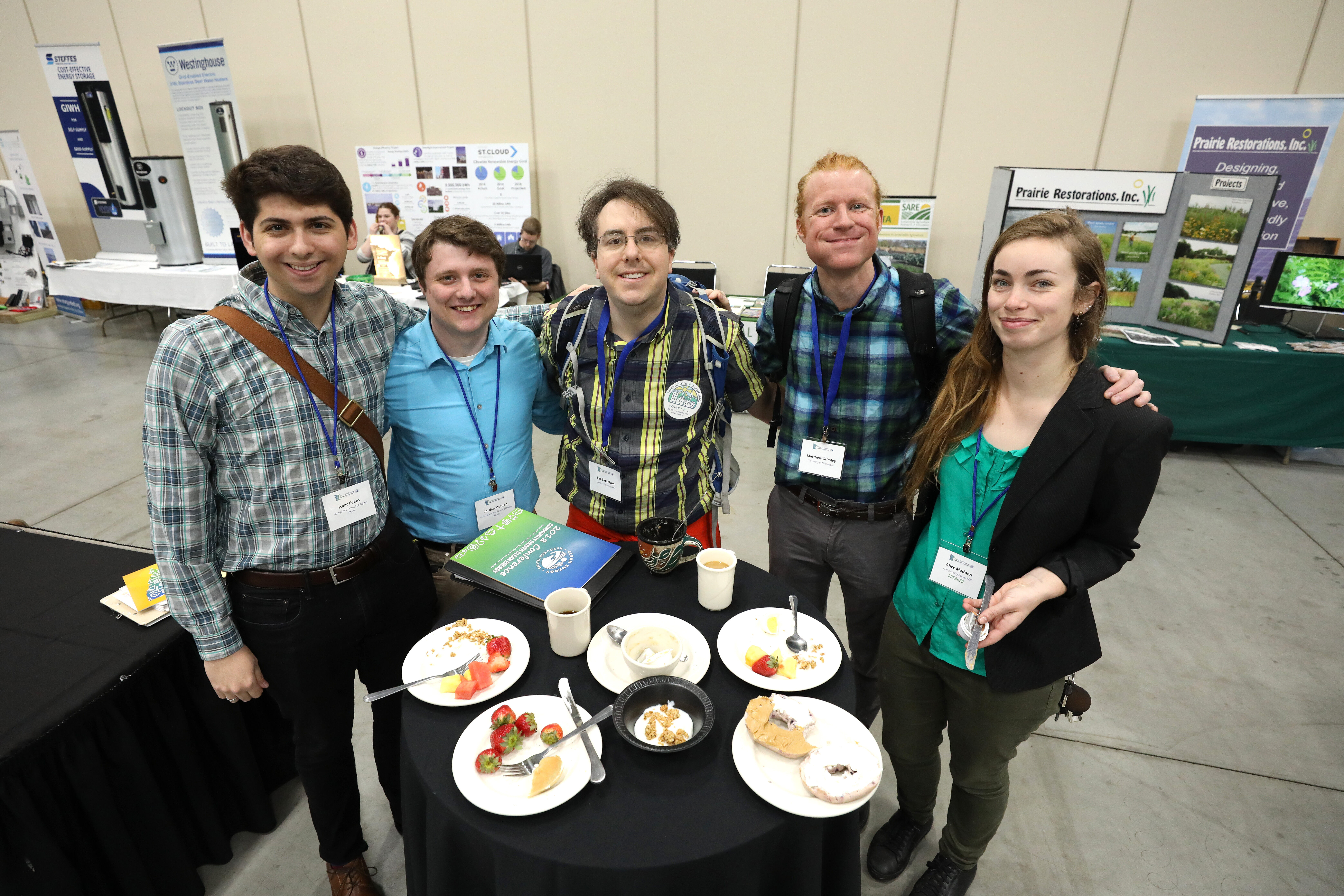

So that's been really exciting work because we've gotten to do this work in partnership and lend some of our capacity where available and what's been really fun is we've also integrated in my research group, a lot of students into this work and created internships out of it and have mentorship pathways for students through all this and engaged other universities in the area, so that their students can participate in some of these projects as well.

What we're really trying to do is find ways for universities to connect with all these really exciting opportunities like electric cooperatives and other kinds of organizations like that.

.png)